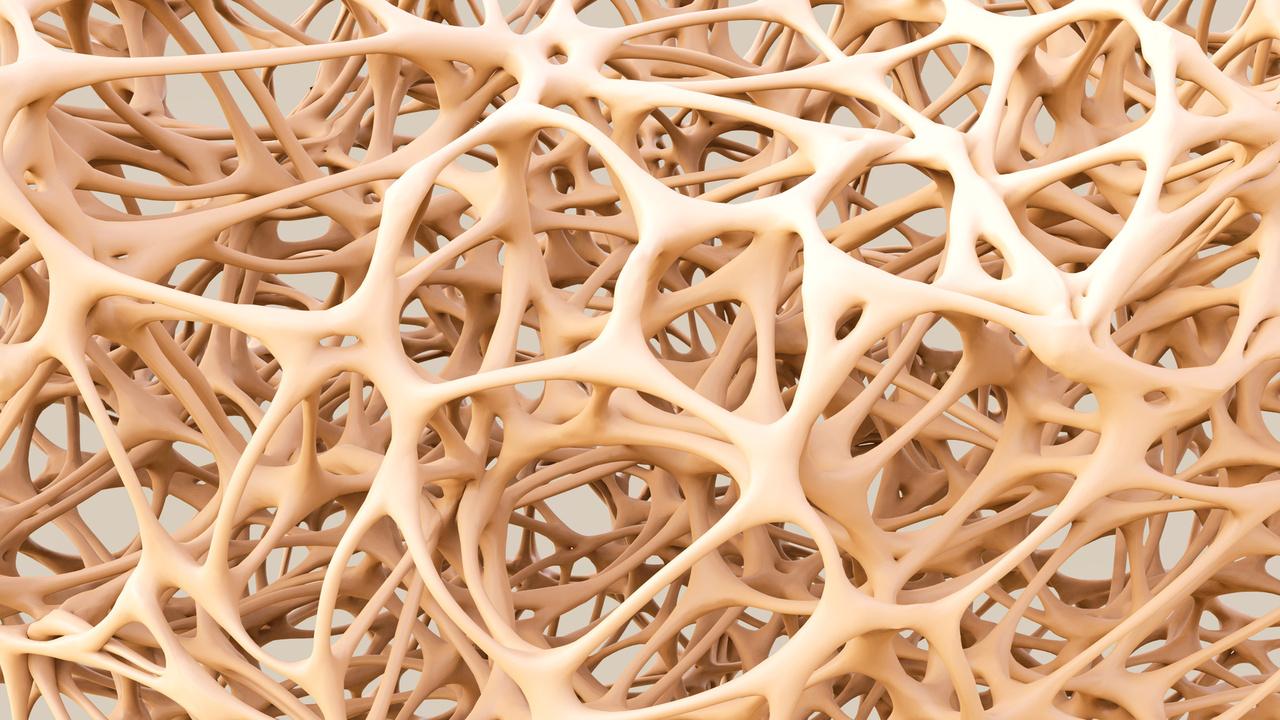

Osteoporosis has emerged as a major public health concern during the past few decades as the population of older Americans has rapidly expanded. Each

year, Americans experience more than 1.5 million fractures due to osteoporosis, resulting in more than 500,000 hospitalizations with a direct cost of more than 20 billion dollars.1

Enormous strides have been made in treating osteoporosis with medication classes such as the bisphosphonates, synthetic estrogens, calcitonin, and, most recently, parathyroid hormone derivatives.2 Although these are excellent medications for treatment of osteoporosis, no current medications are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of osteoporosis.

For years, calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and exercise have been the mainstays of preventive therapy, but studies have indicated only marginal improvement in slowing of bone loss.3<8 Recent laboratory experiments have examined the possible role of plant-derived compounds known as phytochemicals in bone remodeling. Conceptually, the idea is that certain phytochemicals increase the rate of bone deposition by osteoblasts and decrease the rate of bone breakdown by osteoclasts. Perhaps the most impressive of these experiments demonstrated that rats fed a diet high in onions experienced a 17.4% increase in bone mineralization for 4 weeks relative to a control group.9,10 At least three

compounds that may be responsible for increasing bone density have been isolated from onions. The first compound is known as F-L-glutamyl-trans-S-1-propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide.11

It is believed to work by inhibiting the osteoclasts that normally break down bone.12 Specifically, F-L-glutamyltrans-S-1-propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide seems to inhibit osteoclastogensis via attenuation of osteoclast-differentiating factor. The other two compounds that may be responsible for increasing bone density are the flavonoids quercetin and kaempferol. Several experiments performed using human cell cultures have demonstrated that these compounds cause premature apoptosis, or programmed cell death in mature osteoclasts.13

Other experiments using similar methods have demonstrated that these compounds stimulate osteoblasts to increase bone deposition.14,15

Given the results of the aforementioned studies, our study question was whether any evidence existed to suggest that onion consumption may increase bone density in vivo in humans. Ecological evidence from the nation of Turkey provides support for this hypothesis. Turkey, which has the lowest osteoporotic fracture rate in Europe, has the highest per capita consumption of onions in the world.16 To put this statement in perspective, from 1994 to 1996, the average American consumed approximately 13.5 lb of onions annually versus 59 lb for the average Turk.17

At the age of 50 years, women in Turkey have a lifetime risk of 1% of developing a hip fracture, whereas in the United States, women have a lifetime risk of 15.8% of developing a hip fracture.18

Although the low fracture risk in Turkey is certainly interesting, it is important to note that many factors, such as exercise, genetics, and overall dietary habits, probably play a role in the low fracture rate, and to attribute too much to any one dietary variable (even onions) could be misleading. Furthermore, one must be careful to avoid inferences about the effect of onion consumption on any given individual based on statistics gathered at the population level.

Based on both the animal model and ecological observation, our hypothesis is that frequent onion consumption is associated with increased bone density. The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is an association between frequent onion consumption in perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women and increased bone density.

METHODS

Study population

We performed an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004, which was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, a division of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.19

We limited our analysis to perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white female participants who were 50 years or older because bone mineral density declines precipitously after age 50 years.20

We specifically chose white women because they have a higher hip fracture risk than African Americans, Hispanics, or Asian/Pacific Islanders.21

We decided to use Bnon-Hispanic[ white rather than white because race and Hispanic ethnicity are two different concepts measured by two different questions in the NHANES.

Because race and ethnicity are two different concepts, Hispanics can be any race, and thus, we felt that it was important to distinguish non-Hispanic whites from Hispanic whites for this study. The NHANES 2003-2004 contains data for 507 perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women 50 years and older, which corresponds to a population sample of 35.7 million. Data were collected between January 2003 and December 2004.

The NHANES survey was designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the noninstitutionalized civilian population of the United States with direct physical examinations and interviews, using a complex multistage, stratified, clustered sampling design. Interviewers obtained information on personal and demographic characteristics by self-reporting or as reported by an informant.

Onion consumption

A food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was added to the NHANES 2003-2004 study which differed from previous NHANES studies. The FFQ was used to collect information on the frequency of food consumption in the previous 12 months. One of the questions on the FFQ involved the frequency of onion consumption.

Specifically, the study participants were asked, "How often did you eat onions?"

The participants were then given a choice of several answers which included "never, 1-6 times per year, 7-11 times per year, 1 time per month, 2-3 times per month, 1 time per week, 2 times per week, 3-4 times per week, 5-6 times per week, 1 time per day and 2 or more times per day.

For the purposes of our analysis, we divided the cohort into four groups. The groups were divided depending on how frequently they consumed onions as follows: less than or equal to once a month, twice a month to twice a week, three

to six times a week, and once a day or more.

Bone density

Whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans were administered in the NHANES mobile examination center. Reasons for exclusion from the DXA examination were as follows: (1) pregnancy (positive urine pregnancy test and/or self-report at the time of the DXA examination) (pregnant women were excluded from the NHANES due to concern about the effect of ionizing radiation on the fetus); (2) self-reported history of radiographic contrast material (barium) use in the past 7 days; (3) self-reported nuclear medicine studies in the past 3 days; and (4) self-reported weight more than 300 lb or height more than 6 ft 5 inches.

The DXA scans provided the bone density of a number of bones as well as a summary measure of total bone density. Each bone density measurement was repeated five times, and an average was taken. For the purposes of the current analysis, we used measurements of bone mineral density reported in grams per centimeter squared rather than t- or z-scores.

Control variables

Several control variables have been identified as risk factors for osteoporosis and thus may be potential cofounders of any relationship between onion consumption and bone density. These variables include age, smoking status, calcium intake, vitamin D level, parathyroid hormone level, exercise intensity, estrogen use, and body mass index.22,23

Smoking status was defined as current smoker or current nonsmoker. Calcium intake was determined using a food diary in milligrams of calcium consumption per day. Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels were assessed by measuring

serum levels. Exercise intensity was determined by self-report as none, moderate, or vigorous. Estrogen use was determined by self-report; participants were classified as either current users or nonusers. Body mass index was assessed in a physical examination and was classified as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Because of the complex survey design of the NHANES, the statistical program SUDAAN (Statistical Software Center, Research Triangle Park, NC) was used to perform all analyses. The complex survey design and weighting allowed us to make nationally representative estimates of the noninstitutionalized population of the United States. To determine whether there was an association between onion

consumption and bone density, an adjusted and unadjusted mean bone density was determined for the total body, lumbar spine, and total leg for each of the onion consumption groups. An analysis of variance was performed for the unadjusted means that compared each of the four onion consumption groups with the group that consumed onions once a month or less. A linear regression was used to find an

adjusted mean bone density (in g/cm2) between the onion consumption groups, controlling for age, smoking status, vitamin D level, parathyroid hormone level, calcium intake, exercise level, estrogen use, and body mass index.

RESULTS

Our cohort consisted of an unweighted sample of 507 perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women 50 years and older (35.7 million weighted). The adjusted total body bone density measured in grams per centimeter squared of perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women 50 years and older increased from 1.02 g/cm2 in the group that consumed onions once a month or less to 1.07 g/cm2 (P G 0.03) in the group that consumed onions once a day or more. The adjusted bone density of the lumbar spine increased from 0.94 g/cm2 in the group that consumed onions once a month or less to 0.99 g/cm2 (P G 0.01) in the group that consumed onions once a day or more.

The adjusted bone density of the total leg increased from 1.05 g/cm2 in the group that consumed onions once a month or less to 1.10 (P G 0.01) in the group that consumed onions once a day or more.

DISCUSSION

As suggested by previous studies, frequent onion consumption seems to be associated with an increased bone density. Although the increase in bone density was only 5%, we believe that the finding is clinically important. To provide

some perspective about the potential clinical importance of these findings, it is instructive to examine two studies from the literature. The first is a large meta-analysis of postmenopausal women that compared hip fracture risk and bone

density in smokers and nonsmokers.24

Although the data were based on a comparison of smokers and nonsmokers, the

results have direct relevance to the interpretation of the present findings about onion consumption. At 60 years, a smoker’s bone density was, on average, 2% less

than that of nonsmokers, and her risk of hip fracture was 17% greater than that of nonsmokers. At the age of 70 years, a smoker’s bone density was 4% less than that of nonsmokers, and her risk of hip fracture was 41% greater than that of nonsmokers. Such findings suggest that even a small difference in bone density has a tremendous effect on fracture risk.

The second study that illustrates the significance of a 5% change in bone density comes from the Women’s Health Study. As part of the Women’s Health Initiative, more than 36,000 women between the ages of 50 and 79 years were given either calcium plus vitamin D or placebo for 7 years.

At the end of the trial, the calcium plus vitamin D group had an overall bone mineral density that was 1% greater than that of the placebo group.7

After reflecting on these studies, we believe that the consumption of raw onion or onion extract may be a useful addition to other treatment modalities for the

prevention of osteoporosis.

Before recommending frequent onion consumption, however, one must consider potential toxicity that may be associated with such consumption. In vitro studies have found genotoxicity resulting from the compound quercetin, which is found in high concentration in onions.25

Although it is possible that onions have genotoxic effects, in vivo experiments using rodents have found no evidence of genotoxicity in doses of up to 2,000 mg/kg of quercetin.26 (Onions contain 2,600 mg/kg of quercetin).27

This study has several noteworthy limitations. Perhaps the most important is our inability to control for all the dietary variables that can contribute to osteoporosis. For example, it is possible that individuals that are frequent onion consumers

are frequent consumers of other foods that may improve bone density. We believe, however, that our understanding of the mechanism through which onions increase bone density compensates for this shortfall. Another weakness of the study design is its reliance on dietary recall; however, the participants of the study did not know that we would be examining the relationship between onion consumption and

bone density when they filled out the survey, which should limit recall bias. Finally, although a standard protocol was used to determine bone density in the NHANES, no specific information was available about the precision of the measurements

or their validity.

Objective: The aim of this study was to determine whether frequent onion consumption is associated with increased bone density in perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women 50 years and older.

Methods: An analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004 was performed.

Perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white female participants (unweighted N = 507; weighted N =35.7 million) were divided into those who consumed onions less than once a month, twice a month to twice a week, three to six times a week, and once a day or more based on self-reported dietary history.

All study participants underwent total body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Results: After controlling for age, body mass index, daily calcium intake, serum vitamin D, serum parathyroid hormone, estrogen use, smoking status, and exercise status, bone density increased as the frequency of onion consumption increased. Individuals who consumed onions once a day or more had an overall bone density that was 5% greater than individuals who consumed onions once a month or less (P G 0.03).

Conclusions: Onion consumption seems to have a beneficial effect on bone density in perimenopausal and postmenopausal non-Hispanic white women 50 years and older. Furthermore, older women who consume onions most frequently may decrease their risk of hip fracture by more than 20% versus those who never consume onions. In conclusion, frequent onion consumption seems to be associated with increased bone density and may be an area for future research. We believe that future research should focus special attention on the association between onion consumption and fracture risk in the hip and lumbar spine.

REFERENCES

1. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson

A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in

the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:465-475.

2. Poole KE, Compston JE. Osteoporosis and its management. BMJ

2006;333:1251-1256.

3. Lohman T, Going S, Pamenter R, et al. Effects of resistance training on

regional and total bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a

randomized prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 1995;10:1015-1024.

4. Kelly PJ, Pocock NA, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Dietary calcium, sex

hormones, and bone mineral density in men. BMJ 1990;300:1361-1364.

5. Wickham CA, Walsh K, Cooper C, et al. Dietary calcium, physical

activity, and risk of hip fracture: a prospective study. BMJ 1989;299:

889-892.

6. Orwoll ES, Oviatt SK, McClung MR, Deftos LJ, Sexton G. The rate of

bone mineral loss in normal men and the effects of calcium and

cholecalciferol supplementation. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:29-34.

7. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D

supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med 2006;354:

669-683.

8. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. High-intensity resistance training and

postmenopausal bone loss: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:

1225-1240.

9. Muhlbauer RC, Li F. Effect of vegetables on bone metabolism. Nature

1999;401:343-344.

10. Muhlbauer RC, Lozano A, Reinli A. Onion and a mixture of vegetables,

salads, and herbs affect bone resorption in the rat by a mechanism

independent of their base excess. J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:1230-1236.

11. Wetli HA, Brenneisen R, Tschudi I, et al. A F-glutamyl peptide isolated

from onion (Allium cepa L.) by bioassay-guided fractionation inhibits

resorption activity of osteoclasts. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:

3408-3414.

12. Tang CH, Huang TH, Chang CS, Fu WM, Yang RS. Water solution of

onion crude powder inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through

ERK, p38 and NF-JB pathways. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:93-103.

13. Wattel A, Kamel S, Prouillet C, et al. Flavonoid quercetin decreases

osteoclastic differentiation induced by RANKL via a mechanism

involving NF-JB and AP-1. J Cell Biochem 2004;92:285-295.

14. Miean KH, Mohamed S. Flavonoid (myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol,

luteolin, and apigenin) content of edible tropical plants. J Agric Food

Chem 2001;49:3106-3112.

15. Prouillet C, Maziere JC, Maziere C, Wattel A, Brazier M, Kamel S.

Stimulatory effect of naturally occurring flavonols quercetin and

kaempferol on alkaline phosphatase activity in MG-63 human osteoblasts

through ERK and estrogen receptor pathway. Biochem Pharmacol

2004;67:1307-1313.

16. Tuzun S, Akarirmak U, Uludag M, Tuzun F, Kullenberg R. Is BMD

sufficient to explain different fracture rates in Sweden and Turkey? J

Clin Densitom 2007;10:285-288.

17. Lucier G. Onions: the sweet smell of success. J Agric Outlook Econ Res

Serv 1998;9:5-8.

18. Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Ogelsby AK.

International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for

risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:1237-1244.

19. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995-

2004. Vital Health Stat 2 2000:1-31.

20. Riggs BL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Mazess RB, Offord KP, Melton LJ

3rd. Differential changes in bone mineral density of the appendicular

and axial skeleton with aging: relationship to spinal osteoporosis. J Clin

Invest 1981;67:328-335.

21. Robbins J, Aragaki AK, Kooperberg C, et al. Factors associated with

5-year risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA 2007;298:

2389-2398.

22. Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk.

Lancet 2002;359:1929-1936.

23. Orwoll ES, Weigel RM, Oviatt SK, McClung MR, Deftos LJ. Calcium

and cholecalciferol: effects of small supplements in normal men. Am J

Clin Nutr 1988;48:127-130.

24. Law MR, Hackshaw AK. A meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone

mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effect.

BMJ 1997;315:841-846.

25. Caria H, Chaveca A, Laires J, et al. Genotoxicity of quercetin in the

micronucleus assay in mouse bone marrow erythrocytes, human

lymphocytes, V79 cell line and identification of kinetochaorecontaining

(crest staining) micronuclei in human lymphocytes. Mutat

Res 1995;343:85-94.

26. Utesch D, Feige K, Dasenbrock J, et al. Evaluation of the potential in

vivo toxicity of quercetin. Mutat Res 2008;654:38-44.

27. Wach A, Pyrzycska K, Biesaga M. Quercetin content in some food and

herbal samples. Food Chem 2005;100:699-704.

Menopause, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2009 759

Authors: By Eric M. Matheson, MD, Arch G. Mainous III, PhD, and Mark A. Carnemolla, BS

ONION CONSUMPTION AND BONE DENSITY IN OLDER WOMEN

received October 10, 2008; revised and accepted November 17, 2008.

From the Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South

Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Funding/support: This work was supported by grant 5 D55HP05150

from the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: None reported.

Address correspondence to: Eric M. Matheson, MD, Department of

Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 295 Calhoun

St., Charleston, SC 29425. E-mail: [email protected]

756 Menopause, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2009

Add a Comment1 Comments

> Calcium intake was determined using a food diary in milligrams of calcium

A good food diary, is the Food And Exercise Diary (WeightLossSoftware.Com).

September 17, 2009 - 8:33pmThis Comment